I have made a Discovery.

Mark was unexpectedly at home today, the rural broadband project restart having been delayed until tomorrow. You will not be surprised to hear that time at home doing things always trumps cash, and so instead of being anxious about the lost wages, actually I was very pleased indeed to have a reprieve.

I was less pleased when he took the kitchen apart. Our friends the Peppers were coming to have dinner with us this evening, if the rain cleared. This meant that it would have been handy to have had a bit of working surface on which I could chop onions and scatter breadcrumbs and generally fill with creative clutter.

The Peppers cooked for us a few nights ago, and it was splendid, so there was a Standard to be met.

Of course it was not a competition, but we were not going to lose.

Whilst the kitchen was filled with bits of about-to-be new work surface, and Mark’s usual collection of lost drill bits and sawdust, I thought I would do some of the nice things that I have wanted to do for ages.

The new kitchen has involved a lot of reorganisation. During this process several things have become homeless.

One of these was the box of shoe-cleaning things.

The only place left to put this was on the shelves at the end of the kitchen unit. This was a handy sort of place, and indeed was the place to which the shoe-cleaning box had naturally migrated, mostly because we don’t use it very often.

The problem was that the box was an old lidless shoe box, containing an unsightly clutter of dirty rags, dubbin, shoe polish, saddle soap and other necessary but unlovely items. I most certainly did not wish to have it on display in my beautiful new kitchen. This is the thing about shelves. Cupboards can be stuffed full of any old gubbins, and it does not even matter if it all falls on your head occasionally.

Shelves give your visitors an insight into your soul.

A few days ago I had the inspired recollection that stuffed in the back of Mark’s shed was an old brown leather suitcase which had once belonged to Mark’s grandfather. It was not really a suitcase, being only about a foot long and hence too small for any suits except for the most vertically challenged, but it was tidy, and handsome, in an ancient dusty sort of way, and had a lid.

I dug it out.

It had been stuffed into the shed because I had refused to have it in the house. It contained a handful of old photographs and papers which we had inherited when Mark’s father took up residence on the top of the grandfather clock. Mark had opened it in the first few days and we had looked inside, only to discover that the contents were so hideously mite-ridden that our faces and hands swelled and itched almost straight away.

Hence I banished it to the shed, wrapped in an insulating layer of plastic.

I thought that the case would make a very good shoe-cleaning case.

It was revoltingly filthy. I do not think that Mark’s father had ever so much as wiped it, and several months in a shed had not helped. I took it into the kitchen and opened it carefully, trying not to disturb anything too much. I lifted the papers out and put them in plastic bags. Then I sprayed the inside of the case liberally with disinfectant, and then with vinegar, and then, just in case, with flea spray.

To my satisfaction, inside the lid was inked an ancient business stamp, which proclaimed that its owner had been Albert Ibbetson. Clogger.

I polished the leather and waxed it, oiled the locks and then set the whole thing by the fire to dry. We have lit the fire, because global warming has let us down badly today.

I took the papers upstairs intending to seal the plastic bags shut and stuff them into some dark corner to save for Oliver to clutter his house up one day. Then curiosity overtook me and I opened them out, carefully.

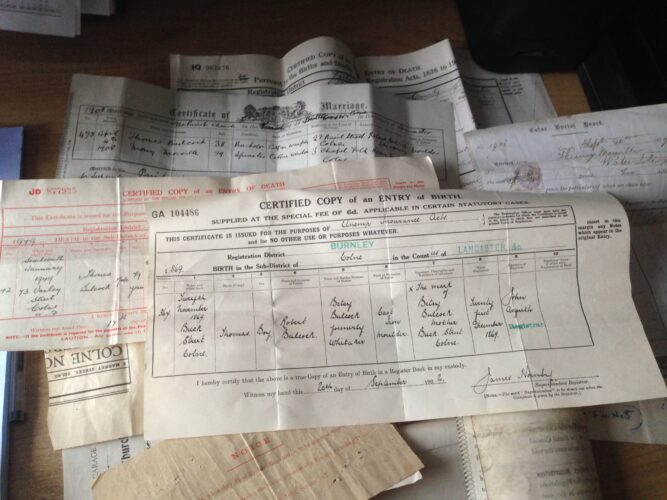

There were birth certificates and marriage certificates and death certificates, all with unfamiliar names. They were not the Ibbetsons, whose background is wealth, and wool, and I was not sure who they were.

After a few minutes I realised that I was looking at the history of Mark’s grandmother’s side of their family.

They went back to 1869. I shouted Mark, and we traced the little history back to his grandmother’s grandparents. There were details of one of his grandmother’s grandmothers, a cotton weaver called Betsey, who could not write her name on her son’s birth certificate, but a shaky X which said beside it, in the Registrar’s flowing handwriting, that it was her mark. There was an invoice for a family crypt, belonging to his grandmother’s other grandfather, and a certificate to say that they owned the tomb in perpetuity and it could be used by all heirs for ever, so if anybody needs to put us somewhere when we pop our clogs, there is a stone box in Colne somewhere which might still have a space and which might be cheap.

When we had finished we could trace the line back for six generations from Oliver, and a quick online look at birth and death records gave us a couple more.

We sealed the papers back into a plastic bag, because they were still horribly itchy, and stuffed them into a dark corner where they would not be damaged by sunlight, and where Oliver can see his ancient family one day.

I showed him this afternoon, but he looked at the 1869 one, and said, seriously: Is that older than you?

The case made the most splendid shoe-cleaning box. We have put it on the shelf and it looks tidy and gleaming and sensible.

We have got a tidy kitchen and some history. How very splendid.

LATER NOTE: The rain did clear and we had an ace dinner.

You will be pleased to hear that it might have been a tie.