We ought to be at work but we are not.

We are in the camper van, in a lay-by in North Yorkshire, and we are not going to go any further.

We are telling ourselves that it is because of the severe weather and the high winds on the A66, but that is a total fib.

It is because we have absolutely had enough for one day. We are not going to go home and unpack. We are not going to go to work. We are not going to pass Go and collect two hundred pounds. We are going to stay where we are and go to sleep.

You will not be surprised to hear that we did not feel very well when we got up this morning. The consequence of last night’s shocking but not unpredictable over-indulgence was that we felt distinctly fragile when the alarm went off.

I was too fragile to drink my coffee.

In the end, of course, we managed to summon up enough determination to start the day, and after we had tidied up, Mark went off to refill the camper van with water and I packed up.

That is to say, I crept around carefully, resolving never to drink again, putting things in bags very gently, and trying not to bend over too much.

Emptying the dishwasher was a challenge.

Mark said that things could be worse, and that Ted had got a nine o’ clock meeting to attend. We agreed that neither of us would have enjoyed that particular adventure, and thought that perhaps things were not so bad.

Of course we had had a brilliant time, Ted and Mrs. Ted are very entertaining company, and we had collapsed into bed with the satisfied sort of feeling that comes from having had a merry night with people whom you like a lot.

All the same, I think I am going to become teetotal from now on.

Once we had arranged our lives into some recognisable order, we showered and changed, and I plastered makeup over my hangover pallor. We loaded everything and the dogs into the camper van, because as you know, today we were going to a funeral.

The camper van is not the obvious choice of transport for a funeral, but it was unavoidable. We parked it at the back of the car park where we thought it might be discreet, but of course it wasn’t really, and sat there looking like a rhinoceros trying to be inconspicuous behind a hollyhock.

The funeral was for a friend of many years ago, a lady called Jackie who had been my housekeeper and general support, childcarer and repository of confidences when the children were young.

Her son Lloyd had been Number Two Daughter’s favourite partner in crime throughout their school days, and her husband had come to drive a taxi with us in the days when we were running a proper business. We had lost touch more recently, but in the past we had been good friends, united in our attempts to keep Lloyd and Number Two Daughter out of prison and in their classrooms. This took more determination than you might think.

In short, they have been a bit of an extension of our family for twenty years, and Jackie was shockingly young to die, not even sixty.

It was nice to see the family, even though it was a funeral. Lloyd has got a son now, almost as old as he was when he and Number Two Daughter were being rascally around Coniston, which was lovely to see, he has become a kindly and gentle father.

We listened to the funeral director telling us that she liked housework and looking after children, and felt terribly sad that her life had been so short. Then we went to say goodbye to the coffin, on its bier in the dreadful red-velvet theatre of the crematorium, touched it in farewell, and it was over.

We went north, because it was Oliver’s school play, and had enough time to sleep on the way. We curled up together in the little camper van bed, and felt guilty relief that today was not our day for saying goodbye to one another.

We changed out of sombre black clothes, somewhat to our relief, especially Mark, who had discovered that his suit trousers had unaccountably shrunk in the wardrobe, and dived into Aysgarth.

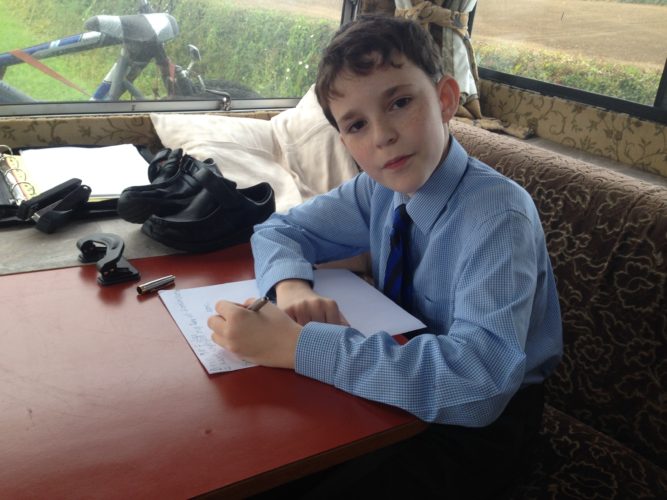

The play was The Hobbit, possibly chosen because of its predominantly male cast, did you know that the word ‘she’ appears only once in the whole book? Anyway, it involved dozens of small boys in enormous false beards and carefully adapted cardigans borrowed from female staff, and it was jolly good.

Oliver was a goblin, besmeared in green face paint, and he and the other boys produced some surprisingly balletic dancing. One of the best things about a boys’ school is that they have no problem at all getting the boys to dance and sing, and one brave hero had been obliged to portray the Queen of the Elves in a long blonde wig.

They were ace, really ace. The music teacher had composed music for the occasion, and the boys twirled and spun and sang and were brilliant. They had built a dragon for the occasion, played by a train of boys with segments, which twisted and curled entirely convincingly, like puppetry.

We loved it, and we clapped until our hands hurt. Oliver came rushing out to see us afterwards. We hugged each other as hard as we could, and Mark got green face paint all over the shoulder of his overcoat.

Eventually a bell rang, and Oliver headed off to the dining room, along with several other small boys, still picking bits of beard off their faces, and we were left alone.

It was nine o’ clock.

We hadn’t eaten anything all day, and were suddenly ravenous. We dashed off to Bedale and bought the very last of the fish and chips just as Jack’s Plaice was closing, and ate them, greasily and urgently, in the back of the camper.

It has been a good day, in a wicked sort of way. I have not been for a walk or to the gym. I have been suffering the consequences of alcoholically bad behaviour. I have had huge quantities of fish and chips for dinner, and now I am not at work.

I don’t care in the least.